Nigeria will hold general elections in early 2027. Long before ballots are cast, however, the country faces a decisive year in 2026: a period in which political competition will intensify while structural crises in security, governance, and livelihoods continue to deepen. Over the past two decades, successive governments have failed to deliver the most basic public good, safety and security. Ordinary Nigerians have experienced expanding insurgency, mass kidnapping, communal violence, daily criminality, economic decline, and a growing perception that the state itself benefits from insecurity. As one Nigerian friend of mine bluntly observes, many citizens now believe that “security officials and politicians have either been compromised or complacent while killings and destruction of livelihood occur.”

Unless 2026 brings visible progress, the 2027 elections risk becoming not a democratic milestone but an accelerant of fragmentation. Major Nigerian online platforms and dailies are full of articles expressing concerns about the upcoming elections. Understanding what Nigeria must confront in the coming year requires recognizing that today’s crises are not temporary shocks but expressions of deep historical and institutional problems, which we can outline below:

A State Built Without a Nation

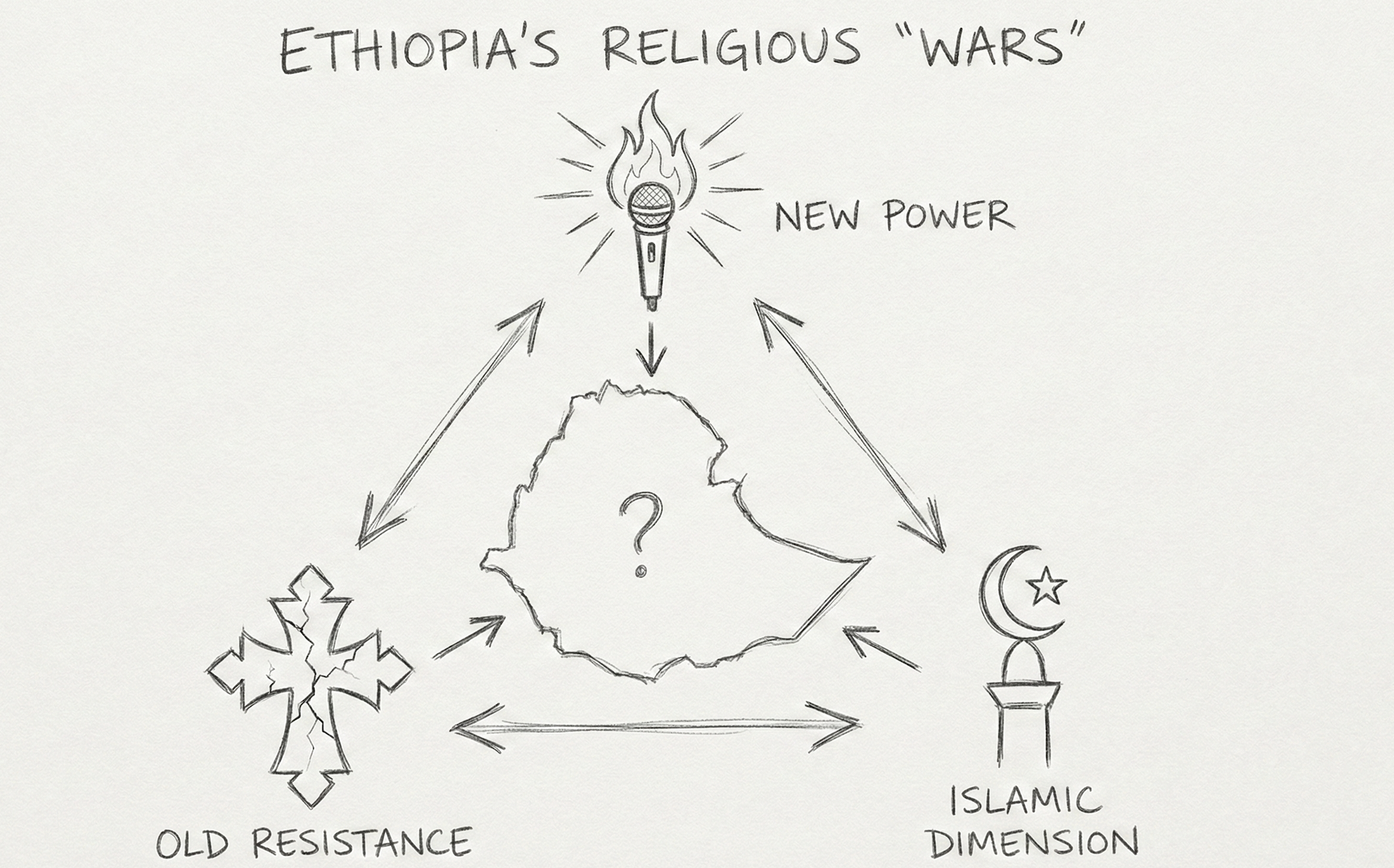

Nigeria’s persistent instability cannot be reduced to a simple Muslim–Christian conflict as is often portrayed and trivialized by the mainstream media. As Nigerian observers themselves emphasize, religion is the surface layer; structural drivers lie beneath. Colonial state formation fused more than 250 ethnic groups and two distinct zones (which had little in common) into a single administrative unit, without building a shared national compact. Northern emirate systems were governed through Islamic institutions; the south developed under coastal Christian missionary influence. British indirect rule elevated selected northern elites while fragmenting southern authority. The result was a state that “was inherited, but not a nation,” a project still unfinished more than sixty years later

Post-independence military rule deepened these distortions. Coups, countercoups, and the Biafran war militarized politics and politicized the armed forces along regional, ethnic, and religious lines. Civilian rule since 1999 has not dismantled these legacies but, in its own way, has civilianized them. Today, distrust among ethnic groups’ representatives and regions, perceptions of biased security deployment, and contestation over federal revenues continue to undermine political legitimacy.

The Security Crises

In the last few years, Nigeria’s security landscape has mutated from a localized insurgency into a nationwide crisis. Since January 2025 alone, more than 2,200 violent incidents have been recorded, exceeding the previous year. Fatalities are driven by jihadist insurgency, banditry, and communal militias, especially in northern regions as well as in the oil-rich regions in the south. In terms of violence, we may indicate at least three violent patterns or systems:

Boko Haram and ISWAP in the northeast: rooted in governance failures and radical religious mobilization, and now operating as sort of “franchises” of global jihadist networks. Their evolution illustrates how local grievances merge with transnational insurgent ecosystems.

Banditry and mass kidnapping in the northwest have transformed insecurity into an economy. Armed groups extract taxes, ransom payments, and control rural trade routes. This is no longer an ideological insurgency but an organized predation flourishing where state authority has receded. Armed groups exist also in the southern states where oil plays a central part of economy.

Farmer–herder conflicts and militia violence in the Middle Belt combine land pressure, climate stress, and identity politics. As Czech field observations note, disputes over land, water, and federal revenue distribution — not theology — form the real backbone of violence

These conflicts now interconnect with Sahelian instability. The collapse of coordinated counterterrorism mechanisms in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger has displaced militant networks southward. Porous borders spanning over 4,000 km allow fighters, weapons, and ideology to flow into Nigeria; therefore, Nigeria’s crisis is no longer local: it is embedded in a West Africa–Sahel security nexus.

The Political Economy of Insecurity

What makes Nigeria’s violence persistent is not only grievance but also incentive. As multiple studies note, senior military and political actors profit from inflated security budgets, opaque procurement, and illicit rents in conflict zones. In other words, insecurity has become a business model. Nigerian observers themselves complain that the army and politicians do not want to solve Boko Haram and other issues that much because it allows them to justify more or less unlimited security spending.

Corruption is not incidental but structural. The rentier oil economy insulates political elites from citizen accountability while funding patronage networks rather than public services. Decades ago, Nigerian historians already described politics as a scramble for rents, contracts, and kickbacks; this so-called prebendial system now permeates security governance.

Security failure directly erodes state legitimacy. Citizens, at least in some parts of the country, increasingly rely on vigilante groups, ethnic militias, and private security. Scholars describe this as “security beyond the state.” Electoral legitimacy also suffers from disputed elections and allegations of fraud, which reinforce perceptions that the leadership lacks a genuine mandate. The 2027 elections will therefore occur under conditions of a deep legitimacy deficit. As some Nigerian analysts warn, the approaching elections are already heightening ethnic and religious tensions and may trigger further violence if grievances remain unaddressed

.

What can Nigeria expect from 2026?

Against this background, 2026 is the last window to alter Nigeria’s trajectory before electoral mobilization peaks. Besides many other things, we may see at least a few priority arenas standing out:

Security Sector Reform

Nigeria’s armed forces are perceived as regionally imbalanced and politically compromised. There have been a few reforms in recent years, driven by efforts to fight corruption and incompetence. The announcement of the creation of state and community police has already sparked debate on social media. One group argues it would help fight terrorism and insurgencies, the other claims that democracy will be threatened. Professionalization, depoliticization, and transparent procurement must follow anyway, otherwise fragmentation will deepen.

Border and Regional Cooperation

As the Sahel crisis spills southward, Nigeria must invest in cross-border intelligence sharing and joint monitoring with coastal West African states. Without regional coordination, militant groups will continue to outpace national responses, particularly given the fact the whole West Africa is undergoing enormous geopolitical changes and challenges.

.

Addressing the War Economy

As long as security budgets remain opaque and conflict zones generate rents, some members of the elite will lack an incentive for peace. Budget transparency, parliamentary oversight of defense procurement, and targeted anti-corruption enforcement in security institutions are essential for the near future, not only 2026. The aim is clear, to signal that the war economy will no longer be tolerated.

Restoring Local Governance and Service Delivery

Insurgency thrives where the state is absent. This explains why, especially in the northern parts of the country, there is space for insurgencies. Rebuilding rural administration, courts, police posts, schools, and clinics in recovered areas is as important as battlefield success. Without visible improvements in livelihoods, displaced populations will remain recruitment reservoirs for armed groups. We may even say that this is the most crucial part of fighting terrorism and violence. And that is also why ad hoc military campaigns bring no solutions to ongoing troubles, because they do not face the real roots.

Managing Electoral Competition

Perhaps most importantly, the government must prepare a credible electoral administration for 2027. Regulating armed political mobilization and guaranteeing impartial deployment of security forces during campaigns will determine whether elections unify or fracture the polity.

The Social Contract

Despite polarizing narratives abroad (such as “Christian genocide” framings in Western political discourse) Nigerians themselves consistently express pragmatic demands. The main needs are functional security forces, fair revenue sharing, infrastructure, education, and genuine anti-corruption measures, not the fake ones. I have heard this simple sentence many times in Nigeria: “What we want is that our own state finally starts working.”

Conclusion

Nigeria’s challenges are immense but not insurmountable. The state is not collapsing but it is rather fragmenting unevenly. The near future offers a narrow opportunity to reverse this trend before electoral mobilization transforms insecurity into existential political conflict.

If reforms stall, the 2027 elections will unfold in a landscape of armed actors, polarized communities, and discredited institutions, a wonderful arena for further disintegration. If, however, Nigeria demonstrates even partial progress in security governance, transparency, and service restoration, it may yet prove that its long-delayed nation-building project remains viable. For external partners, the whole message is quite clear, supporting Nigerian-led institutional reform and regional security cooperation will yield far greater dividends than some ad hoc or episodic counterterrorism assistance or intervention. Nigeria does not need so much saving from outside but rather a state that finally works from within.

.png)

.jpeg)